One of the big questions I face on a regular basis is if chemistry photography is "dead" now that we have digital photography. My short answer is that they still make stuff out of the earth, don't they? If ceramics has existed and survived for centuries despite the development of newer technologies, surely photography's roughly 150 year run could last a little bit longer?

But this leads me to another question. Is digital photography simply the newest technology of photography, or is it actually a new medium?

In many ways the advent of digital imaging mirrors that of chemistry photography. Photography as we know it was invented in the 1830's when Louis Daguerre developed the ability to produce a lasting image from light sensitive materials in a relatively short period of time (minutes instead of hours as Niepce had done in the 1820's).

The invention of photography forever changed the way we looked at the recording of images and likenesses. In 1800 if you wanted your portrait, you had it painted or rendered in some way by hand. But by 1850 if you wanted a portrait, you had a choice. And this choice changed not only our relationship to photography, but also to painting. Painting had been the means by which we recorded the world around us, now painting was "liberated" from the task of simply recording reality.

This is not to say that this was a conscious choice at the time, but if you look at painting styles between 1850 and 1950 you will see a definite progression away from faithful recording to interpretive and expressive image making. In other words, photography created a choice for painting to be about something else besides "recording."

But early photography also had a problem. A problem of taxonomy. What was photography? What was its role? Photography was not really seen by most as a fine art in the 19th century. Those who attempted this usually did so by mimicking an existing medium, painting, to give it credibility. Ironically, it was the characteristics that made photography unique - the sharpness, the ability to accurately record - that kept the medium from being embraced as something "creative."

It wasn't until the Soviet Avant Garde movement of the early 20th century that photography was appreciated for it's unique aesthetic and technical abilities. The optical lens can see and record space with a different depth and film exposure can treat light in a unique way. Only then, some argue, did photography come into it's own as a medium.

What then is unique to digital imaging? Are we treating this medium to the standards of another? I argue that we have culled digital imaging to mimic photography. Digital images are comprised of pixels and yet we shun images that are "pixely." Is digital imaging following in the path of chemistry photography? First emulating another medium and slowly coming into its own?

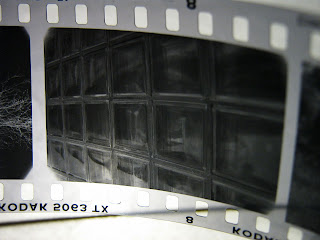

Digital imaging is fundamentally different than chemistry photography because the capture method has changed. Throughout what Martin Lister would call the "short history of photography" the technology has changed but the capture process has always remained the same. That is to say that it was always a chemical process utilizing light sensitive silver. But digital imaging is an electronic process in which light waves are converted to binary data (this is a super-simplified explanation of course). Right now the goal with digital images is to emulate film photography but it doesn't have to be so. As the design group Eboy says, "Pixels are beautiful."

image credit: mnsc